The Industrialization of Education: Phase One, 1870-1930

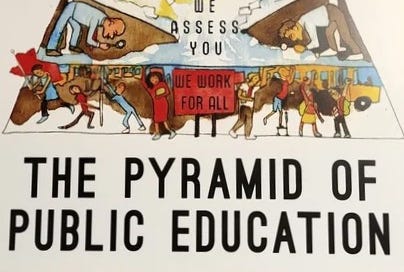

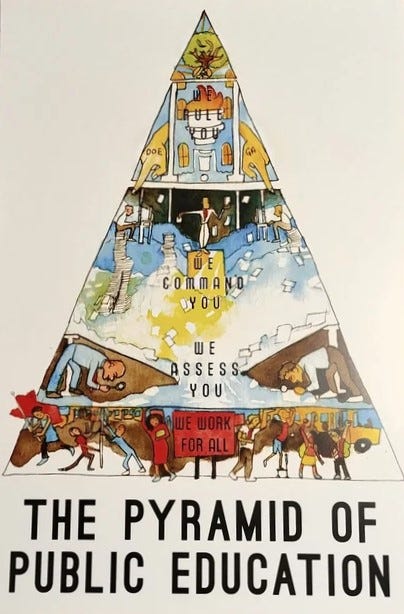

A Taxonomy of Class Power in Schools, Libraries, and Museums

This three-part study of the education industry by and for education workers is adapted from a zine by Angry Education Workers, an ephemeral collective of instructional and support staff in schools, museums, libraries, and archives. The full text can be found on the Angry Education Workers Substack or downloaded in printable booklet form below:

The Industrialization of Education - printable booklet version

The Industrialization of Education - digital version

Phase One, 1870-1930

Two ideals are struggling for supremacy in American life today: one is the industrial ideal dominating through the supremacy of commercialism, which subordinates the worker to the product and the machine; the other, the ideal of democracy, the ideal of the educators, which places humanity above all machines, and demands that all activity shall be the expression of life. If this ideal of the educators cannot be carried over into the industrial field then the ideal of industrialism will be carried over into the school. Those two ideals can no more continue to exist in American life than our nation could have continued half slave and half free. If the school cannot bring joy to the work of the world, the joy must go out of its own life, and work in the school, as in the industrial field, will become drudgery..…

It will be well indeed if the teachers have the courage of their convictions and face all that the labor unions have faced with the same courage and perseverance.

-Margaret Haley, “Why Teachers Should Organize,” 1904 speech to the National Education Association convention

Industrial Ecology

America never deindustrialized. It just scaled down its manufacturing sector while industrializing other parts of the economy—like education. We have to expand our concept of production beyond the factory floor if we’re to ever have any hope of understanding ourselves and our situations as workers in an industry with the same exploitation and disparities of power, privilege, and resources as any other. Education has transformed from local, community-based schools to an industry in the same way the retail, service, logistics, legal, healthcare, hospitality, railroad, construction, maritime, agricultural, and more industries have. A critical inspection of the history of American education reveals how corporations, politicians, and ‘the voters’ have designed schools, libraries, archives, museums, and research facilities as factories to extract profit from education workers and students. But first, we must answer some fundamental questions:

What is an industry? What is industrialization?

What comprises the education industry?

How did the emergence and development of capitalist production lead to the industrialization of education?

What does pre-industrialized education look like?

What is capital? And what is capitalism? How do we analyze class in the 21st Century?

In education, who are the workers? And who are the bosses?

We’ll deal with the last question first. Among the workers we find janitors, teachers, paraprofessionals, interventionists, sports coaches, librarians, substitutes, adjuncts, graduate workers, docents, food service workers, library techs, and SPED teachers. Among the bosses we find administrative bureaucracies like the Department of Education, charter school management companies, school boards, and distant education corporations like Scholastic, Pearson, or Great Minds. Principals, assistant principals, deans, academic coaches, library directors, museum directors, and other administrators form a managerial middle class. They’re the fulcrum which continues to pry education from the public sector. Often forgotten in that middle class are education researchers, policy writers, and curriculum developers.

If you’re reading this, you’re probably a worker. This text is for all education workers—whether you’re a teacher, a security guard, a library associate, front office staff, or whatever else. If you work in a place geared towards education, this will hopefully help you analyze your corner of the industry in a broader framework. That said, K-12 schools are the center of gravity for this piece. They formed the bedrock institutions of the industry, and to this day, almost half of the entire industry’s economic output is in K-12 schools. I will weave the history of post-secondary education, libraries and museums in whenever possible, but I encourage others to write their own inquiries on the industrialization of other educational sectors.

Capitalism is a system that relies on the movement of capital to produce economic wealth. Capital comes in two forms: money and commodity. The money form is just that: money, including bank deposits, hard cash, and other liquid assets. The commodity form includes resources that can be bought and sold on the market with money. Its role is to bring the labor power of workers from lots of different places together to cooperate in generating dazzling wealth on a scale never before possible in human history. This wealth is generated collectively—by dozens, then hundreds, and then thousands—by workers in factories, schools, warehouses, farms, and other production facilities around a now globalized world.

But that socially created wealth is not distributed socially. Instead, the employer, whose only use is that they have more money than everyone else, takes the product of workers’ labor and sells it for a profit. Only part of that profit ever goes back to the worker. For the factory owner, the restaurateur, or the school board member, the impulse is to pay workers as little as possible and extract the maximum amount of labor. Some call this a day’s wages for a day’s work. It’s more accurate call this exploitation. All profits are effectively unpaid wages. Bosses squeeze more surplus value—time spent working more than you’d need to survive—out of the workers by reducing wages and lengthening work hours, or by making those hours more intense and demanding. Academic professionals and big capitalists united to extract surplus labor value from education workers.

Big capitalists—corporate executives, banking magnates, and the like—are less than one percent of the population. But they call all the important shots, though most of them haven’t worked in any of the industries they own shares in. Surrounding them is the middle class. People use that term sloppily in America. Often, they’re referring to anyone with a college degree, or any degree of comfort or social standing. Middle class seems like more of a cultural mindset than a coherent class. There is, however, actually a middle class we can point to and analyze: the small business owners, small fry landlords, preachers, and professionals such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, and scientists (AngryWorkers 2020). In education these are tenured professors and administrators of schools, libraries, and museums. These folks usually place in the top fifteen to twenty percent, income-wise. The rest, 80 percent, is the working class and lower strata.1

Supporters of capitalism usually reply that the machines, facilities, and tools were provided by the capitalist. Who built the machines and buildings? Who crafted the tools? Workers did. Machines “copied the artisan’s physical movements and transferred it onto an apparatus, such as the weaving loom or the spinning machine. Major investment was necessary for engines to move these machines, while workers who operated them could be paid much less…and the independent artisans died a rapid social death” (AngryWorkers 2019).

Another reply is that capitalists take on the financial risk of owning the operation. Who dies when the machine fucks up or the employer refuses to follow covid protocols? Workers! Who loses when privatized schools without proper oversight fail? Workers and students! We build the whole world with our combined labor. But capitalists use industrialized production to steal our labor and our time for their own private profit.

Industrial Taxonomy

An industry is a collection of production facilities, companies, job roles, and pieces of infrastructure across a geographical area assembled to produce a common set of goods and services. Every industry encompasses three main layers: production, distribution, and consumption. Through these layers, industries interact with each other. Workers in a factory are not usually involved with distribution. Instead, logistics workers at Amazon, UPS, USPS, and FedEx bridge the gap between producer and consumer. The printing and publishing industry manufactures textbooks, encyclopedias, and other books for the education system. The tech industry, to name another example, produces computers, tablets, and digital tools for schools, libraries, and museums.

Industrialization is when an agricultural society changes into one where a minutely crafted division of labor, huge urban populations, and the application of technology allows for mass production of goods and services. Three conditions are needed for industrialization to occur:

A centralized workforce practicing division of labor. Tasks must be divided into the smallest possible units. Labor is also divided along lines of gender, race, type of work (blue collar versus white collar).

Primitive accumulation. Also known as initial or background accumulation, it’s an ongoing process of hoarding wealth that can be reinvested. Marx described this beginning with slow economic growth and technological innovation in the Medieval Period, along with the “enclosing” of land that threw the peasants into the cities. This accumulation reaches new heights with slavery and colonialism. The fledgling industry of Early Modern Europe, for example, was mainly fed through imperialist looting and enslaved labor (Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture 2003).

Production must become increasingly consolidated in fewer hands. By tying disparate, small to medium sized production units—like cottage industry2—into massive ones, Early Modern merchants and landowners generated enough capital and productive capacity for the emergence of large, monopolistic firms. Such firms can effectively circulate commodities on a national or international scale. By exploiting workers and driving down costs throughout this process of circulation, those who have money to invest accumulate capital (Marx 1867).

What exactly comprises this education industry? To figure that out, we must deduce what its main product is. It manufactures a person who has been inculcated with the knowledge, ideology, discipline, and culture that primes them to serve the whims of business owners and politicians. The education industry helps reproduce capitalism itself. Education also serves as a connecting point—a node—between different industries and social groups with varying levels of power.

Daycare workers, nannies, and babysitters—along with women consigned to housework and unpaid childcare—share with teachers the burden of carrying our society across generations. Libraries, museums, and schools are constant, essential sites of family events and social services. Schools free up millions of people for full time work. Museums produce cultural services for school age children and families that help reproduce knowledge and civic traditions.

With that in mind, the education industry includes: public, charter, and private pre-Kindergarten through 12th grade schools; post-secondary institutions like colleges, universities, and trade schools; non-profits, foundations, and government departments geared towards education research, funding, and curriculum development; corporate and government job training and lifelong learning facilities; cultural institutions like museums and libraries; and the amorphous armies of gig tutors and tutoring companies that surround the entire industry.

Education workers carry out production, such as lesson planning, exhibit construction, classroom setup, program creation, or teaching. Other times, these workers distribute products or render services. Then, there are education ‘non-profits’ like Great Minds, which originally created the Common Core curriculum. These institutions develop the curriculum tools teachers and other education workers use to shape the raw material—students—into the workers, managers, and owners of the future. They are to schools what engineers are to factories.

The industrialization of education began in the 1840s. Since then, businesspeople have used politicians to structure education along the lines of private industry. Under the guise of ‘reform,’ these succeeding generations of ruling class capitalists—from factory owners to startup bros—have shaped and reshaped education. Since 1992, capitalists have peeled away huge swathes of education from the public sector entirely. The goal is the end of free public education altogether.

The Early History of Education in America

Pre-industrialized education looks like the one-room schoolhouses of American legend. Or the small community schools taught by ministers in the New England colonies. Tribal communities around the globe pass down knowledge and traditions in communal, but informal ways. Preceding industrializing library systems, there were private subscription libraries for elite European men (Hillary and Abbott 2015). The first museums were the private collections of rich people, who began to selectively display them as “cabinets of curiosity” in the 1500s (Bennett 1995). Then there are the parochial schools of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries (Gross 2018). We’ll examine some of these in more detail.

Dorchester, Massachusetts opened the first taxpayer funded school in 1639. Massachusetts Bay, along with most Northeastern colonies, passed compulsory attendance laws in 1642, and required parents to teach children how to read (Goldstein 2014) (Easterling 2013). But education was not an industry yet—it could not be. The earliest rumblings of industrialization were still barely felt, even in textiles.

Early school systems were scattered, community oriented, local in scope, and taught by ministers, not a dedicated teaching workforce (Goldstein, 2013). Primitive accumulation in education was underway. Spoils from the violent colonization of the Americas had been flowing for hundreds of years. Schools were built on land stolen from indigenous tribes like the Massachuset, Wampanoag, and Nauset tribes with stolen bodies.

Land encompassing what is now Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin—wrenched from the British in the final stages of America’s blood drenched birth—was called the Northwest Territory (Black 2020). These were lands inhabited by native nations like the Delaware, Miami, Potawatomi, and Shawnee, whose homelands were auctioned off by a broke central government to white settlers for free (Black 2020).

Education was bound up in this dispossession. In fact, “the Ordinances placed public education at the literal center of the nation’s plan for geographic expansion and statehood in the territories…Every new town had to set aside one-ninth of its land and one-third of its natural resources for the financial support of public education” (Black 2020, 63). Land and natural resources that would need to be forcibly seized by armed settlers—inside and outside the military. In 1836, in the days of the Trail of Tears and the expansion of slavery westward, “the nation made an enormous new financial investment in public education. Tariffs, the collection of war debts, and the sale of federal lands generated an ‘unprecedented surplus’” (Black 2020, 69) that the federal government handed to the states. Nearly all the money in the “people’s inheritance” got spent on public education. Public education allowed the white elite to integrate lower class white settlers into a political-economic system that exploited them.

Despite the still localized nature of education, regional teaching workforces had formed by the 1820s. Most schoolmasters were badly paid men with no curriculum. Education reformers of the day, like Harriet Beecher, ridiculed them as drunk, tyrannical, and abusive—though they were likely “less cruel or stupid than frustrated. They were struggling with educational neglect…and lack of funding” (Goldstein 2014, 21).3 A patchwork labor force like this could hardly be called a modern proletariat.4

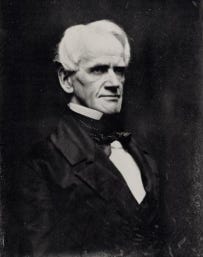

Horace Mann was a Whig politician in Massachusetts with connections to religious social liberals and “fiscally cautious northeastern business interests” (Goldstein 2014, 23). In 1837, he became secretary of the first Board of Education, achieving compulsory schooling for the state’s children. Mann set up the first teacher colleges, then called normal schools, in 1840. There, teachers in training learned teaching as a craft, with standardized practices and subject matters. He only accepted women to save money. As the common schools movement5 caused local governments across the Northeast and Midwest to build schools, the size of the teaching workforce ballooned (Gross 2018). By 1873, most of these teachers were women (Goldstein 2014).

Now that there were teachers, the question naturally arose: what would all the students learn? Teachers never had any say. Instead, “politicians and business leaders, the kind of men more concerned with educating the next generation of voters and workers than in fostering intellectuals” (Goldstein 2014, 28) held sway over education reformers like Horace Mann and Catherine Beecher. Teachers and schools were “expected to ‘strengthen the moral character of children, reinvigorate the work ethic, spread civic and republican values, and along the way teach a common curriculum to ensure a literate and unified public’” (Shelton 2017, 80).

As teaching became overwhelmingly “women’s work” through the mid-19th Century, teachers simultaneously experienced proletarianization.6 Most of the women coming into teaching at that time were white and the daughters of farmers, blue collar urban workers, or stable middle class families. All these women had few job prospects outside teaching. These women faced patriarchal and capitalist barriers as they sought financial, and, synonymously, legal and emotional independence. Without this material basis for asserting themselves against families, people—especially women—become vulnerable to abusive dynamics. Women moving into the teaching workforce had to navigate these difficulties with little support.

This represents a profound shift at a critical time across an American Empire that was conquering westward at a dizzying pace. Teachers would not be professionals in the sense that doctors and lawyers were (and are). They did not have the ability to self-govern and regulate like genuine professionals had (Goldstein 2014). Instead, they would be workers. American teachers had little say in school operations, pay, hours, or what they taught.

The First Phase of Industrialization in Education, 1890-1930

School enrollment, along with library and museum construction, spiked after the American Civil War, peaking from 1890-1930. The number of students rose from 12.7 million to nearly 26 million. By 1920, there were over 3,500 public library branches nationwide. Since the end of the Civil War, immigration from the Eastern and Southern margins of Europe, combined with unprecedented industrialization and urbanization, had changed the empire.

A nation of mostly Western European descended protestants treated Catholic immigrants like an invasive species whose illiteracy would hamper economic growth (Gross 2018). Protestant business leaders saw public education as a tool to assimilate them, especially as private parochial Catholic schools sprung up like weeds—sustained almost entirely through donations from local parish communities and outside the bounds of state regulation (Gross 2018). Parochial schools offered a quasi-industrial alternative between the pre-industrial forms of the past and the industrialized models of public schooling of the future. In the 1920s, these parochial schools would accept regulation in exchange for crucial governmental funding, effectively incorporating them into the education industry and marketplace (Gross 2018).

By 1883, the Republican Party had passed compulsory attendance laws7 in the fourteen Southern states and required Southern states to make education a constitutional right to rejoin the Union (Gross 2018). They wanted the state to use compulsory education as a tool to construct “national growth and unity” (Gross 2018, 64). With a devastated nation to rebuild, compulsory attendance could assimilate defeated Confederates, newly emancipated Black Americans, and immigrants “into the greater body politic” (Gross 2018, 65). Education, then, became part of life, an integral part of the social reproduction process of the American nation-state.

Meanwhile, library workers were mobilized towards the same objective and were “key partners” in the Americanization Movement (Hillary and Abbot 2015). By mandating nighttime English language and civics classes at libraries, state legislatures thought they could transmit upper class American values to immigrants. Outside the libraries, native tongues were banned in certain settings and immigrants targeted for mob violence.

By the Civil War, philanthropy was well established in education. Charlotte Forten was a black teacher who moved from New York to Port Royal in the South Carolina Sea Islands to teach newly freed Black children. Neither she nor her students received what they needed, so she “wrote to philanthropists in Philadelphia to send picture books for toddlers” (Goldstein 2014, 51). While the common schools movement had tucked most education into the public sector,8 anti-tax sentiment by business owners left it underfunded. Philanthropy helped the capitalist class put down roots in education on their terms.

Andrew Carnegie was single-handedly responsible for financing the construction of nearly 3,000 public and academic libraries. Requests for funding from various towns and universities swamped him. Towns had to put down ten percent themselves and provide the land for free. This leaves communities in a position of feeling ‘grateful’ to a benevolent capitalist who is really just boosting his public image. His actions contributed to a sense of “vocational awe” among library workers, which is “the set of ideas, values, and assumptions librarians have about themselves and the profession that result in notions that libraries as institutions are inherently good, sacred notions, and therefore beyond critique” (Ettarh 2018). Library workers then work themselves raw with smiles on their faces. Philanthropy also drove education reform efforts.

Boards of Education hired hundreds of thousands of teachers. Chicago and New York City were epicenters of this expansion. By this time, the Second Industrial Revolution had conjured the juggernaut of capital into being. Mass industry necessitated a managerial class, who cooperated with the rich to enforce discipline.

Chicago was the city on the hill of a “thriving reform scene, driven by innovative ideas in social sciences and progressive politics” (Goldstein 2014, 68). The University of Chicago was the nucleus of this reformist atom. The president was chosen by the mayor for the school board, and was charged with “centralizing the curriculum, pedagogy, and administrative structure of the public schools” (Goldstein 2014, 69). Men like him supported Taylorism.9 They pushed for technocratic management for schools and libraries, with workers and the voters excluded from curriculum policy. Of course, these academics believed they should be the ones making those decisions. Elite academics like college presidents and other administrators “forged an alliance with business leaders, who liked the idea of top-down, expert management of schools, yet deplored paying higher taxes to fund public education” (Goldstein 2014, 68).

Private companies used their political and economic power to siphon public funds and profit off education. Chicago Public Schools had 15,000 education workers throughout the city, which made it the city's largest employer. The government and “professional elites” of the time “reorganized the Chicago public schools and, like other school districts across the nation, placed them under the control of education and business experts” (Lyons 2008, 11).

Without autonomy and paid abysmally—about $13,000 a year in today’s dollars, an amount frozen in place for 20 years—the teaching workforce of the city was powerless. Women elementary school teachers faced overcrowded classrooms, sexist pay schedules, and corrupt municipal political machines. During this time, “teachers were sometimes paid not in wages, but in ‘warrants’ promising future pay, which teachers had to cajole grocers and landlords to accept in lieu of cash” (Goldstein 2014, 68). Most teachers in the early 20th Century were single women, meaning they did not have husbands and fathers to fall back on in the same ways a lot of other women could.

Precarity placed teachers among other working-class women, who do not have the freedom and access to power that bourgeois10 or middle-class women have. Former University of Chicago president William Rainey Harper canceled a paltry raise for teachers to drive women out of teaching. In response to protests, Rainey said “they should be happy they earned as much as his wife’s maid” (Goldstein 2014, 69). Susan B. Anthony—a teacher herself—articulated a more working class centered feminism. Anthony said in a letter that when spreading the word about women’s rights meetings, she wanted “particular effort made to call out the teachers, seamstresses, and wage-earning women generally. It is for them, rather than for the wives and daughters of the rich, that I labor” (Goldstein 2014, 38).

Teachers’ politics lined up closely with those of industrial workers, and still do (Lampson 1919, 200-1) (Lyons 2008) (Thompson 2014). Unfortunately, reformers from upper class backgrounds were the ones who wielded the scythe of political power in America. Taylorist, “scientific management” schemes were at the heart of their ideological program (Goldstein 2014) (Lyons 2008). The goal was total control of the workforce. Political leaders routed working class children into vocational education. Corporations dodged taxes brazenly. Schools around the city fell into disrepair from chronic underfunding. After decades of tax evasion, and a corrupt patronage-based spending glut by CPS, the city and school system were nearly broke by 1929 (Lyons 2018, 12).

In this context, class struggle within the education industry began, first in Chicago, and then most areas east of the Mississippi (Martin 1999).

Class Struggle during the First Wave of Industrialization

By following the thread of the labor movement within education during this period—including how it was nearly crushed—we can understand another angle of education industrialization. Where there are workers, there is class struggle. Workers responded to industrialization by forming unions. Their surplus labor, stolen through the underfunding of schools and the inevitable longer and harder workdays that followed, allowed for private profit. We will begin in 1916, when several localized teachers’ unions amalgamated into the American Federation of Teachers (AFT).

While the movement began entirely in cities with at least 30,000 people, it then spread like wildfire (Cook 1921). Teacher organization was now a national movement, sharply dividing the academic-managerial types of their day. Some university presidents and professors advocated reform to undercut the motivation for rebellion and prevent class conflict in a public-school system that served “all classes” (Cook 1921).

By 1920, the AFT counted 10,000 teachers in 180 locals, tripling its membership and more than doubling the number of locals (Martin 1999). But membership fell to under 5,000 in 1930. Above all, “strong opposition to teacher unionism by local school boards, school administrators, some teachers, and especially the business community” was the cause (Martin 1999, 200). Additionally, “yellow dog” contracts,11 the AFT “no strike” pledge, and low salaries hobbled organization (Martin 1999, 200-1). While the previous two decades brought victories for the CFT, with lawsuits to recover hidden corporate tax revenue and ensure equal opportunity for all within the schools (Martin 1999), the 1920s brought a withering defeat.

Attrition rates for AFT affiliated unions was high. Small, rural branches struggled to survive staff turnover and union busting. From 1920-21 alone, the number of operating locals dropped from 180 to 122 (Cook 1921). Even so, the AFT survived by clinging to urban strongholds.

Teachers' unions found solid footing in most major American cities by 1920, and as early as 1897 in Chicago. Founded by normally “docile” Chicago elementary school teachers, the CTF turned heads in 1902 when it affiliated not with the National Education Association (NEA), but the Chicago Federation of Labor (CFL) (Lyons 2008). Despite this militancy, professionalism as a construct encouraged many teachers to view themselves as middle class public servants instead of workers.

The history of the NEA embodies this. For 100 years the NEA “portrayed itself as a professional organization little interested in bettering teachers’ wages or attaining collective bargaining rights” (Lyons 2008). Even so, they counted 200,000 members, increasingly schoolteachers, by the end of the 1920s (Cain 2009). In 1954 NEA membership topped 560,000 (Dewing 1969), consistently ahead of the AFT.

Ultimately, the NEA was not controlled by its rank and file, which overwhelmingly comprised women K-12 teachers. Instead, “school administrators, the largely male group...clearly maintained control of the association” through 1972 (Urban 2001). The NEA had, and has, a centralized organizational structure on the national and state levels, while the AFT functions with autonomous branches like the mainstream labor movement. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the NEA could be called a proper union after a member upsurge that drove administrators out.

Cornering the Market, 1880-1930

“Education entrepreneurs” prey on high poverty, colonized communities, as well as many poor white communities (Rooks 2017). In the early 20th Century, their common ancestors among the industrial magnates were men like John D. Rockefeller and Julius Rosenwald. They funded school construction for Black children across the South. It is no coincidence that this is during the same period that Jim Crow law and the white vigilantes with their nooses and red lines were forcing Black Americans into segregated zones.

So, while white philanthropists who had “made their money in cotton, steel, railroads, minerals, and financial services” (Rooks 2017, 56) shaped the teaching workforce, they were also making their own captive customer bases out of Black families. Compulsory attendance laws aided their efforts. To these customers—mostly workers or sharecroppers—they “proposed educational curricula and forms offered only to Blacks and the poor” (Rooks 2017, 50). Rockefeller and Rosenwald “understood how…important an educated Black population was for the future economic prospects of businesses in that region, if not in the entire country” (Rooks 2017, 50). Their solution was to gather the cheapest labor power, buildings, and land, then combine it with the coercive power of the state to build a workforce prepared for brutal industrial capitalist workplace routines.

Southern legislatures—implementing their segregationist and terroristic agendas—used their power to divert dwindling federal money away from Black schools and teachers towards white ones. Northern white philanthropy remained the only real school funding source for Southern Black schools. The Julius Rosenwald Building Fund sent agents around the South to collect “all they thought they had” (Rooks 2017, 49) from Black communities. This money was meant for building schools and included a “match” from the foundation if a town raised enough starting capital. These rich whites now took advantage of Black, students, teachers, and communities who had no other options besides underfunded, overcrowded schools. Black communities footed much of the bill and in exchange got some of the worst schools in the entire world as their benefactors raked in cash. Yet again, white Northern industrialists grew rich on capital they could then reinvest in their own companies, or into further business opportunities within education.

Following the Money

In the 1920s, corruption was rife, with Republican administrations awarding “contracts for school construction and equipment to business groups that had direct links to city politicians” (Lyons 2008, 12). Here, we have another crossover between industries: education and construction. The Board of Education leased out land it owned in downtown Chicago to the The Chicago Tribune and other “business friends” for dirt cheap prices (Lyons 2008, 13). Finances were atrocious, so the Board kept the system afloat by going into ever deeper debt to banks through financial wizardry (Lyons 2008, 13). All of these examples reveal the pathways money followed as it circulated through the education system and generated profits for corporate and political elites.

Understanding the circular movement of commodities—goods placed on the market to sell for a profit—and how it generates capital is crucial. There are two types of commodity circulation: commodity-money-commodity (C-M-C) and money-commodity-money (M-C-M). Commodity-money-commodity is what normal people do. We sell a commodity—for us that is labor-power or something we made—in exchange for money, which we use to buy other commodities that we then use. Money-commodity-money on the other hand, means a person is holding onto the commodity until it is the right time to sell it to generate more money. A capitalist exchanges money for a house, not to live in, but to sell or rent for a higher value than what they acquired it for—to generate profit. Capital is the original value plus a change in value, which is added by exploited workers’ skill, creativity, and cooperation. Capitalists endlessly repeat this process, accumulating capital off the backs of billions of workers (Marx 1867).

Education itself has become a commodity that can be speculated and profited on, represented by the various degrees and certificates a person can use to enhance the value of their labor—if the gamble pays off. Student loan companies, universities, governments, and other stakeholders place bets on the potential futures of students. Will they finish high school? Drop out of college? Graduate but fall through the cracks into low-wage labor? Default on their loans? Work themselves to the bone to pay their loans? Become high-income workers who pay them back, no problem? Hit it big and create their own hotshot companies? No matter what, some rich person’s pocket gets lined. America is a casino, and the house makes the rules.

Equipment, workers, land, and buildings comprise the initial investment of money. Education workers refine the raw materials: the students, until they are ready to enter the job market. Everyone must then refine themselves to match up to the competition or fail and die. Women are doubly exploited. One set of people—mothers—perform reproductive labor for society. Their children were extracted as raw materials and working-class women teachers were then exploited to refine them.

Industries such as education, defense, and healthcare feature vast sums of public money flowing through them. This is great for private capitalists. Initial investment money comes from the public, and the product is simply handed over to the capitalist, for free. Lucrative building contracts, access to public land for cheap, and overlooked corporate tax evasion have a cost, one paid by education workers and students. Profit is unpaid wages. By reducing their expenses and soaking up public tax funds on the backs of teachers, the money returns to capitalists at a greater value. It absorbs new value from labor.

The only opposition corporate elites faced was from nascent teachers' unions like the Chicago Teachers Federation and “lady labor slugger” Margaret Haley, who were barred from striking by their own union leaders.

Then the Great Depression hit. To many, it appeared as if the resources for public education had evaporated overnight. In response, the Citizens’ Committee on Public Expenditures (CCPE) formed in 1932, counting in its ranks the city’s “leading bankers, merchants, and industrialists” (Lyons 2008, 30-31). Their top priority was cutting education costs, so they usurped functions of city government relating to public schooling. Meanwhile, other public sector workers continued to receive job and salary protections—thanks to the spoils system of the city—and corporations had dodged tens of millions in taxes. The horrendous consequences immediately became clear as teachers went unpaid for months (Lyons 2008). Teachers paid for these cuts with their labor.

Conclusions

Ultimately, all these struggles illustrate the growing role class power had in shaping curriculum, staff discipline, and student population. The industrial ruling class of the country did not directly own the public education system. Counter-intuitively, the location of education in the public sector played a central role in its industrialization—not just in this first phase, but up through today—by allowing capitalists to bring the coercive power of the state directly to bear on workers, students, and their communities while placing the burden of cost on the public.

When analyzing the history of public education in America, it becomes obvious how public money consistently served private capital. This is clear in the union busting frenzy of the 1920s. It is also easy to see this in the way corporations used the state to rob the schools and harvest the next generations of workers in their wider system of speculation, profit, and plunder. Teachers at underfunded schools then had to work harder and longer for less pay. All the while, the professional middle class remained complicit while crafting the architecture of our exploitation—assembling standardized tests, developing one-size-fits-all curriculum, and eroding job security through arbitrary evaluations. Our students, especially those from poor or colonized backgrounds, are siloed into schools where they and the staff have few, or no, other options through the power of the law. The isolation and atomizing of these communities enabled the capitalist class and their cronies in the government to generate capital from public education, reshaping it along the lines of industrial management and production.

Find all sources cited or referred to here: https://tinyurl.com/checkreferencepage

Stay tuned for Phase Two!

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed reading this, please help spread the word.

Forest of Doors is happy to take submissions from its readers. For inquiries, please leave a comment and send an e-mail to comradebroguy@gmail.com. The e-mail isn’t checked often, so the comment helps.

The houseless (though many have jobs), incarcerated workers, long term unemployed, gang members, and other classes at the margins of the mainstream economy.

“Where people would work at home or in small workshops. They often worked as independent artisans, using their own tools, e.g. for spinning, weaving or wood work. Men, women and other family members worked together. They depended on the big business owners for the supply of raw material, such as wool. These early workers organised themselves, they went on strike if prices for their products dropped or if bread prices increased too much. They stopped working as soon as they had earned enough” (AngryWorkers 2019).

An interesting place where an echo of such attacks, which were fairly widespread at the time, crops up is in the fictional story of Ichabod Crane in Legends of Sleepy Hollow. For more information about this classic work of American literature, its historical context, and relevance, see Brotato’s “Thoughts on Sleepy Hollow” (2022).

The vast majority who do not own their own means of production, like a farm or a business, and have to work for a wage or salary to survive, and depend on the whims of employers for their standard of living.

The common schools movement was a dispersed movement for creating “common schools” that would educate all children regardless of class, race, or religion.

The process of turning a population into waged or salaried workers.

At this time, these laws mostly mandated children between seven and fifteen attend school for at least three to four months.

Robert Gross, a Washington D.C. private school teacher and expert on parochial schools, argues this is largely what created the idea of a “public sector” in the first place.

Taylorism is also known as “scientific management theory,” and was developed by Fred Taylor in the early 20th Century as a way to more efficiently manage workers.

Capitalist, upper class.

Pledges in employee contracts not to join unions.