They Breathe is a game by The Working Parts, released in 2014.

The title is most likely a reference to John Carpenter's 1988 film They Live - which I haven't actually seen. What I know of They Live comes from Slavoj Zizek's analysis of it in The Pervert's Guide to Ideology, a skimmed Wikipedia summary, and a little under three decades of U.S. cultural osmosis. However, I'm pretty sure I get the gist: it's a movie about conspiracy, where the powerful exploit the powerless in a way that is by and large invisible.

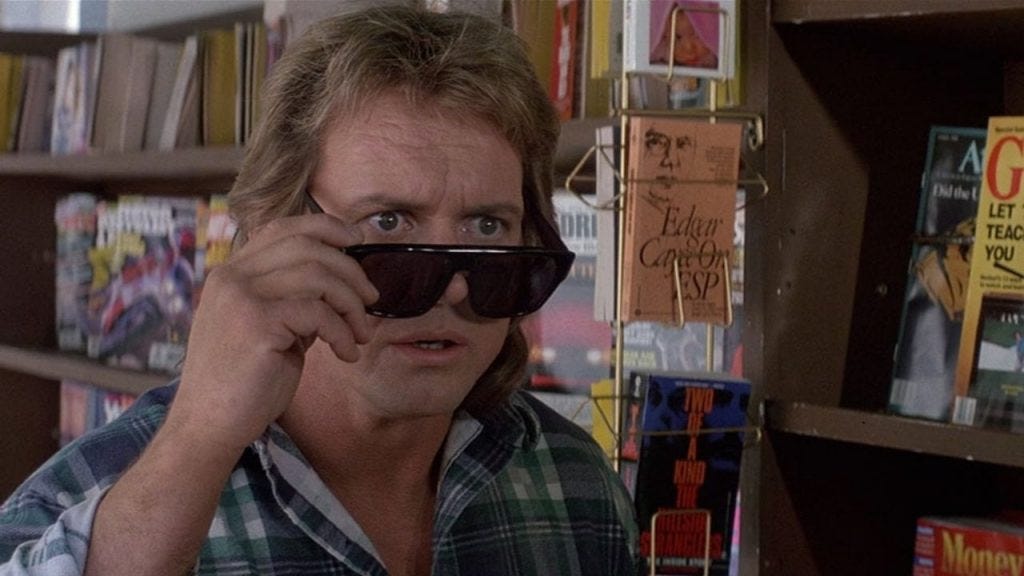

In They Live, our protagonist unveils the media's subliminal messages promoting mindless consumption and complacency. How does he do it? By donning a pair of shades. The glasses also reveal the perpetrators of these harmful messages: aliens, of course! They look just like regular people, but the glasses reveal their true form: ghoulish, corrupted humanoids.

The revelation - the unmasking of the conspiracy, enlightenment as to the true nature of the world - is sudden, abrupt, almost immediate. The work of figuring it out is done for you, all you need to do is wear the glasses, which, as Slavoj Zizek says, function as "critique of ideology glasses."

This is magic, in a way. It is, unfortunately, too simple. A brilliant and compelling plot device, to be sure; a good entry point for thinking about and exploring the roles of ideology, class, and more in our society? Certainly; but as a model or a guide, it would fall flat.

There is no argument or evidence in the real world as forcefully persuasive as those glasses. If there was, how terrifying that would be! - but it would make social revolution a lot quicker, easier, and tidier than it ever could be in real life - and that’s exactly how so much of our media about this topic portrays it.

But no one has a perfect, unadulterated worldview, untinged by ideology. And no one, for that matter, can ever voice a flawless critique. Any critique of one ideology will necessarily have its roots in some other ideology. This isn't to say "morality is relative, there is no right or wrong, it's all subjective." Critique of ideology is necessary even if ideology itself is inescapable - without getting into it, some ideologies are better than others - depending on your values, themselves a product of ideology. Yes, it’s ideology all the way down. But not with the glasses, they’d have you think! The critique provided by the glasses is truly supernatural; with the appearance of impartiality, rather than leading one to question what they see, it fundamentally changes what they see. If we assume that objective perception doesn’t exist, that the glasses aren’t showing us the Truth but rather a truth, then they function to not just critique ideology but to change it instantly. From this standpoint, they are brainwash glasses, or radicalization glasses. Even if we assume that the glasses do show the absolute objective Truth, then they’re still magic glasses that skip over all the actual work.

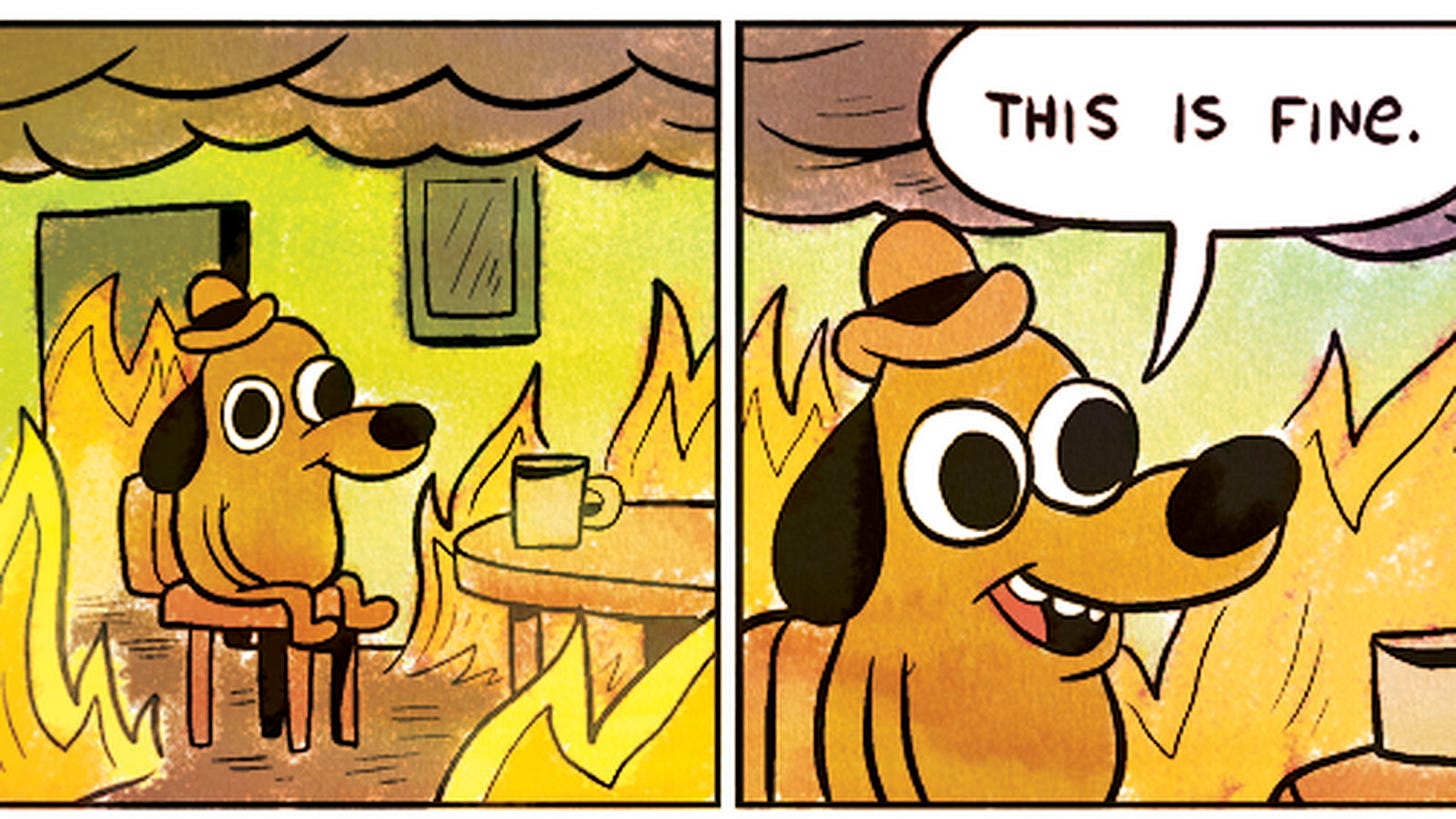

Questioning the nature of the world around you requires observation and inquisition, which take time, effort, and fortitude. One's own ideology will resist scrutiny the same way a body will resist disease. But many of us are tired from life and work, too tired to put up much resistance of our own against ideology's lull, even when evidence is dangled before us that should challenge everything.

I maintain that this isn't out of love for ignorance. Cognitive dissonance is a coping mechanism for when our actions don't/can't align with our values. Rather accept a world where we have little power to fight back against wrongdoing, where fighting is difficult or impossible, one might go into denial. "This is fine."

I have been told that, for instance, my iPhone is made in a sweatshop. I think of this frequently, and yet I still use my iPhone, and when it breaks there's a good chance I will replace it with a new one. Why? I know I should throw it away. But it's comfortable, everyone uses something like it so I can convince myself my own impact is minimal, and if I take a strong moral stance on it people will get defensive - consider how people react to vegans. I don't think this would happen if they didn't know that veganism makes a good amount of moral sense, and yet they themselves have not followed. It is unpleasant to be confronted with your own cowardice. It is easier to think that everyone is a coward, and so it doesn't matter.

But we can only even get as far as this when the information needed to critique dominant ideology is accessible. In order to live in denial, there must be information to deny. At times, the facts might be hard to come by, or obscured by competing theories. Such obfuscation could even be the (mal)intent of those in power: either shielding the innocent masses for their own good, or just shielding the system from any threat the masses could potentially pose to it. When this happens, ideologies become invisible like the air we breathe. It's unquestionable "common sense." Contrast the ideological security when there is widespread agreement over scant information, to the confusion and chaos that comes from disagreement over scant information. When enough doubt exists, we end up in the "post-truth" hellscape of today, people living in wildly different realities, hermetically sealed against critique. In both cases, when people lack information they inhabit fantasies that ultimately benefit the ruling class, either by reinforcing the status quo or by isolating each man to his own ideological island, her own quixotic crusade against an imagined or inflated social ill. People on the ideological fringes will have a hard time coming together - a unifying ideology like QAnon is the exception that proves the rule.

In fiction, the truth about the world can be made simple to process and obtain, at least for our lucky protagonists. They Live has its glasses; The Matrix has its red pill. Again, these are compelling plot devices, but we need to remember that that's what they are: plot devices, cutting through the ideological fog like butter in order to skip over the time it'd usually take to get everyone on board with dismantling the system. It is narratively efficient and visually impactful - elements that make for a good movie.

However, we must acknowledge that there is a downside to making it look easy. The fact is that, for most people, most of the time, ignorance is not a choice. Most people live with the sense that something is wrong, but few have any idea what. And without certainty, people have a hard time coming together to take action, and there are certainly those who benefit from our collective inaction.

By making the attainment of knowledge look as easy as flipping a switch, it's possible to come to the conclusion that people just don't want to know. It is a short distance from there to blaming people for their own oppression and thinking people don't want or deserve to be saved, or to seeing people as passive objects, as children or sheep who just don't know what's good for them, lying in wait for some mastermind or hero to set things aright. The first is antisocial; the latter can be a justification for denying people choice and imposing one's will upon them. I’ve glimpsed this attitude in progressives who have the time, the money, and the education to research, reflect upon, and ultimately criticize dominant ideologies. Friends, please, use your privilege for good, but check your superiority complex at the door.

Consider the early stages of the "Hero's Journey." I am not a huge proponent of this storytelling model myself, but neither am I quite opposed to it; it is a useful analytical tool, especially when we're considering the underlying assumptions and psychological effects of stories.

In the Hero's Journey, the protagonist is situated in his "Ordinary World" - the life he is accustomed to and happy with. Then, he receives a Call to Adventure, in which he is invited to leave this World behind. This, he usually refuses. Rather than be born into a harsh new world, he would rather remain in the womb, safe and familiar. Then, as these things go, some event transpires that makes it impossible for the protagonist to stay in the Ordinary World: Luke loses his aunt and uncle; Bilbo's "Tookishness" prevails over his "Bagginsy" inertia; Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden of Eden. "If I look back, I am lost," as proclaimed by a certain Khaleesi. It is a staple of the Bildungsroman and any story featuring a character coming of age, a common element in adventure stories.

This part of the hero's journey, and the "reluctant hero" trope in general, are metaphors for growing pains. I think that narratively, they are powerful and resonant. We relate to them because, yes, growing up, and change in general, is painful. Unlike in our own lives, we can look on at stories ironically from the outside and know what our heroes need to do. And from that standpoint, it always looks easy. Distilling this common - dare I say universal? - experience into a single, snappy event is one of the Hero’s Journey’s strengths - and also, I’ll argue, its weakness.

Growing up is a lifelong process. Enlightenment does not come all at once, in a single "aha!" moment. Nor does Knowledge follow a taste of a Forbidden Fruit.

The metaphor is condensed to the point of abstraction. Oftentimes the focus is not given to the process of change itself, but the buildup and the aftermath. There's nothing wrong with telling such stories, but it seems that the process of change is underrepresented in storytelling. Under- or overrepresentation can affect our sense of what's important or true. In this case, might stories be teaching us to expect abrupt turnabouts and linear paths to victory?

In stories, the end of the first act is often marked by the inciting incident, which shoves the protagonist through the door of their Ordinary World in order to follow the Call to Adventure. But in real life, don't we linger, sighing, in the vestibule? Don't we open the door, see the rain, and say "not today, maybe tomorrow"? Don't we take our first steps and then stop, sometimes for months or years, before continuing on our way? And isn't the door sometimes locked from the outside, and needs breaking down? From its structure, the Hero’s Journey would have you think that these people will never grow up without a great deal of force and a pair of horse blinders to keep them from looking back.

Yet when heroes are prisoners of their own Ordinary World, of the metaphorical womb of ignorance, the door they must break down seems to be made of cardboard, yielding with the first or second shove. In They Live, the obstacle of ignorance is transformed from a mountain to a molehill, paving a straight path to revolution. As much as I like the concept for what it is, when we look at it this way it is no better than schlock, disconnected from our lives.

A problem with this stage of the Hero's Journey, and how it comes up in They Live and The Matrix: voluntary and involuntary change coincide and may be unfortunately conflated. There is little distinction, in terms of how they will function in a story, between a character who is immature and needs to grow and a character who has been deeply misled their entire life and needs to uncover the truth. And to compare an involuntarily cultivated ignorance to immaturity is unfair. It infantilizes people, painting the powerful as the patrons, or shepherds, of the world.

In The Pervert's Guide, Zizek draws our attention to a famous fight scene where the protagonist is trying to force the glasses on his friend. The protagonist's friend is essentially refusing the Call to Adventure. There is, Zizek points out, no reason for him to resist a pair of glasses like this, and it is almost as if he has some awareness of what the glasses represent.

He is fighting to stay in his Ordinary World. The glasses make it impossible to return. There is no need to explain or convince - by merely showing him the truth, the Ordinary World is shattered, is shed like so much dead skin. A New World is born from the ashes.1

When you show someone the truth, there is still the matter of individual exegesis - this is something these films actually agree with me on. One of the truest parts of The Matrix and They Live is that, despite the magic glasses and pills, some people see the same incontrovertible evidence and decide it is better to side with the oppressors. Even when the truth is absolutely evident, there isn’t a single, clear path forward. You can, in fact, get lost, even if (maybe especially if) you don’t look back.

Anyway: In They Breathe you are shown an (eco)system at its surface level, and slowly descend through its depths, unpeeling the layers as you go. Almost no instruction or context is given to the player. You plunge right in and, as you play, naturally form a working theory about how the world works. As you delve deeper, you are forced to keep amending and questioning that theory - that ideology.

They Breathe does not hold your hand when it comes to interpretation: it makes you do all the hard work yourself. Not only is this more rewarding for players, it is a more realistic portrayal of how we interface with the world through ideology.

The revelation of They Live seems to be to be immediate and certain. As soon as the glasses are on, poof! You grok oppression pretty damn well, and you know exactly where to point your finger when it comes to placing the blame. There is horror (or perhaps, more aptly, terror) in the realization that everything you know is a lie, but because there is no room for doubt, you can easily feel the righteous indignance necessary to resist authority, with zeal for fuel.

The revelation of They Breathe is slow and uncertain, and therefore uncomfortable, unnerving. While I'm fairly confident in my own interpretation, after playing through the game twice and spending hours in reflection, I don't believe in it with unwavering certainty, and it doesn't ring with the obviousness we sometimes expect of truth. Because there is doubt and confusion, therein lies the creeping, dreadful sensation more appropriately called horror.

In other words, They Live will give you thrills, but They Breathe will give you chills.

It perhaps is no coincidence that the 1988 film, much to the dismay of its director, has been adopted by neonazis and antisemites as an allegory for Jewish control. These extremists are galvanized by simple, all-encompassing narratives. They rightly feel something is wrong, but in grasping for an answer their anxious fingers close around the neck of a scapegoat. I think this sort of explanation - this sort of ideology - makes people feel purposeful and driven. It gets them angry and ready to fight back, because it doesn't leave room for being held back by doubts. This sort of actionability is enviable, but the uncritical adoption of radical ideology is not. I would rather be hesitant than misled.

I feel bigots would have a harder time latching onto They Breathe for a number of reasons - the imagery and symbolism of aliens in human guises has been historically very appealing to antisemites, for instance, and such imagery is absent from They Breathe - more on this in Part 2, I think. But most of all, They Breathe doesn't propose to you that there are simple answers to be found. It doesn't shy away from portraying a system of complex evil - so complex that, while the suffering inflicted by this system is undoubtable, the evil intent of that system can be called into question, and in some ways made palatable. If it doesn't make it palatable, it at the very least doesn't invigorate you to feel like you're fighting the good fight, and there are few opportunities to feel heroic. If anything, if it weren't a game, these discoveries might discourage action, either making you long for ignorance, or making you feel the system is too complex to know where to even begin your attack. Thankfully, it is a game,2 and while you aren't told what to think, you are given only one direction to go: down, down, down. Perhaps our protagonist, a frog (unofficially?) named Glen, knows something we don't. Ultimately, the answers we seek are not on the surface, but lie deeper.

In conclusion: I don’t hate the movies I’m using in this comparison. I haven’t even seen They Live, but it seems like a really great idea from a progressive filmmaker. And I actually love The Matrix. But I feel we can use these films to notice a trend in how we tell stories about oppression, and better appreciate They Breathe for the way it bucks that trend.

Hollywood, in true American fashion, loves a good revolution. I think it’s unrealistic to expect that these movies hold instructional value - they are too abstract. That’s not a bad thing, as abstraction lets us talk about complex ideas in narrative form to begin with. It can be a bad thing if the point of the movie is so vague that people at opposite ends of the political spectrum can both see themselves in your protagonists’ struggle. Perhaps some of this is unavoidable consequence of the medium. A movie is not a manifesto. A video game is not a manifesto. They are more like treatments of ideas or like dreams: generally about a subject, but not strictly so - shadow discourse through association games and subtext. We love stories for their obliqueness, not even in spite of them - it is a feature, not a bug.

There is nothing wrong with a single story portraying revolution in a simple manner, but when multiple stories portray it in the same way it becomes a broader narrative. Even if the individual storytellers have the best intentions, the effect of that broader narrative can be quite pernicious. In this case, we have to ask how and if the stories within this narrative even benefit us - if they nourish the ideas and values they claim to endorse, or if, like empty calories, they give us our fill on only a superficial level - feeding us the aesthetics rather than the ethics of revolution?

In Part 2 I will talk about my interpretation of They Breathe. If my description has intrigued you, be warned that Part 2 will necessarily contain spoilers, as I need to provide textual evidence for my reading and not just talk out of my ass. I highly encourage playing it - it's cheap, on multiple platforms including Steam (where I first heard of it and wishlisted it) and Switch (where I eventually bought and played it), and will only take about 30 minutes of your life, unless you're like me and you replay it as preparation for writing an article about it. The Switch version, at least, has a sort of rudimentary co-op mode available - I only call it rudimentary because I'm unsure if the difficulty/number of enemies is scaled to account for the presence of player 2, but the experience is basically the same aside from the added challenge of needing to share resources and screen space with a companion - this co-op mode at least allowed me to have the novel experience of showing my partner and seeing his reaction.

And it has frogs, so: automatic 10/10.

Thanks for reading! If you want to check out my other stuff, check out my carrd!

Forest of Doors is happy to take submissions from its readers. For inquiries, please leave a comment and send an e-mail to comradebroguy@gmail.com.

A key point to understand here: the shift in the Ordinary World does not need to be a physical one to spur the protagonist onward. Ideological shifts are just as, if not more, important - in many ways, your ideology is your world. (For more on this, see "What is Worldbuilding," an article written by Loreguy and myself.)

Perhaps we need more media that provide us with low-stakes opportunities to feel discouragement. In small doses, we can practice processing negative emotions and build up resilience. This is not unlike Aristotle’s idea of catharsis, which is, like, the oldest idea in all of lit crit. I’m not saying anything particularly new, is what I’m saying.

Looks like I'll need to go out and play this game before part 2 comes out!

amazing and sober analysis!